# So You Want to Build an MVP

Preface

Through my work as an Entrepreneur in Residence at the Youngstown Business Incubator, I get a lot of questions about building MVPs. This blog post is my attempt to capture as much of the advice I typically give in one place.

If you are a Northeast Ohio based entrepreneur looking for resources, consider applying to become a YBI portfolio company. YBI portfolio companies get access to EiRs like myself, among other resources.

PS: Prefer video?

Here’s a recording of me giving the talk this blog post is based upon.

Some caveats

First, I believe that it’s important to understand the backgrounds of the people you take advice from, so you can understand the context of the advice. I myself have taken advice from people whose backgrounds I didn’t fully understand, and it led to poor execution. As such, I encourage you to take a look at my resume before continuing.

Second, most of this advice is based on failures. My own startup failed, only making $600 but burning $40,000 of my own money and investment. Very little of this advice is based on successes. (Though BlastPoint has seen some awesome success lately).

Third, I want to emphasize that the advice below is entirely based on opinion. The path to startup success can be counterintuitive, and as such it can be difficult to differentiate between good and bad advice, and very tempting to take advice that sounds good but is probably bad.

Fourth, given the above, I urge you to instead read something from someone who has been there, done that, and successfully exited. Preferably multiple times. Maybe something from the YC Startup Library?

What is an MVP?

Minimum Viable Product

”A version of a product with just enough features to be usable by early customers who can then provide feedback for future product development.” ~The Internet

Goals of an MVP

- Proves the riskiest part(s) of your startup.

- Starts your “iteration engine”.

- Built…

- Quickly

- Cheaply

- Maintainably

- Intentionally

Common Startup Risks

- Are people interested in this?

- Are people willing to pay for this?

- Are people willing to pay enough for this?

- Do I have a viable way to market?

- Is this technically feasible?

Fun activity: Write down these risks and rank them.

Start with your biggest risk

Your goal as an entrepreneur is to strategically de-risk your startup, starting with the most risky parts.

You may not need an MVP to prove your startup’s next largest risk.

MVPs are expensive and inherently risky

Building an MVP requires significant time, money, and effort. If you build the wrong thing, you’ll waste all three. Worse, you might miss your market window or burn through your runway before finding product-market fit.

Before writing a single line of code, focus on learning everything you can about your market, customers, and problem space. The more you learn upfront, the less likely you are to build something nobody wants.

Alternatives to building an MVP

- ”Wizard of Oz”ing an MVP.

- Do things manually for your first customers.

- Automate manual processes with spreadsheets / Airtable / low-code as you go.

- Use something off the shelf / white label.

- Create a clickable prototype design (Figma) and show your customers.

- Pre-sell the product (letters of intent, pre-sign ups, etc - preferably for money).

- Lots more, get creative.

Some Exceptions

- You can build your own MVP - it’s cheaper and less risky to build yourself.

- You are in a deep tech space (where your value comes from breaking a technical barrier, like quantum computing or advanced AI) - difficult to Wizard of Oz, typically requires a specialized, technical founder.

Whatever you do, optimize for learning

At any point, if you don’t feel like you are learning, you should probably change strategy.

My MVP Process

- Scope

- Visual Design

- Technical Design

- Estimation

- Implementation

Scope

”The objectives and requirements needed to complete a project.” ~The Internet

Thinking of MVPs as a de-risking tool is a strategy to help determine the “scope” of your MVP.

What is the minimum you need to build to de-risk your next riskiest thing?

Why keep scope small?

- Shorten time to de-risk

- Lower cost

- Less risk of project going over budget

- Less risk of potential customers losing interest

- Less to throw away if your MVP doesn’t fit client requirements

Once you decide on scope, you should do your absolute best not to change it until after getting customer feedback.

Once the MVP is built, you can iterate.

Examples of scope:

- List of features (ex: Authentication, Posting to Feed, Groups)

- List of user stories (ex: “As a user, I need to be able to share my contact details with other users.“)

Either approach is good, it depends on how much creative control you want to give to the designer in the next step (which may be yourself!)

Visual Design

The goal of the visual design step is to have a visual reference that allows everyone involved to make sure they are on the same page (ie, agree on scope).

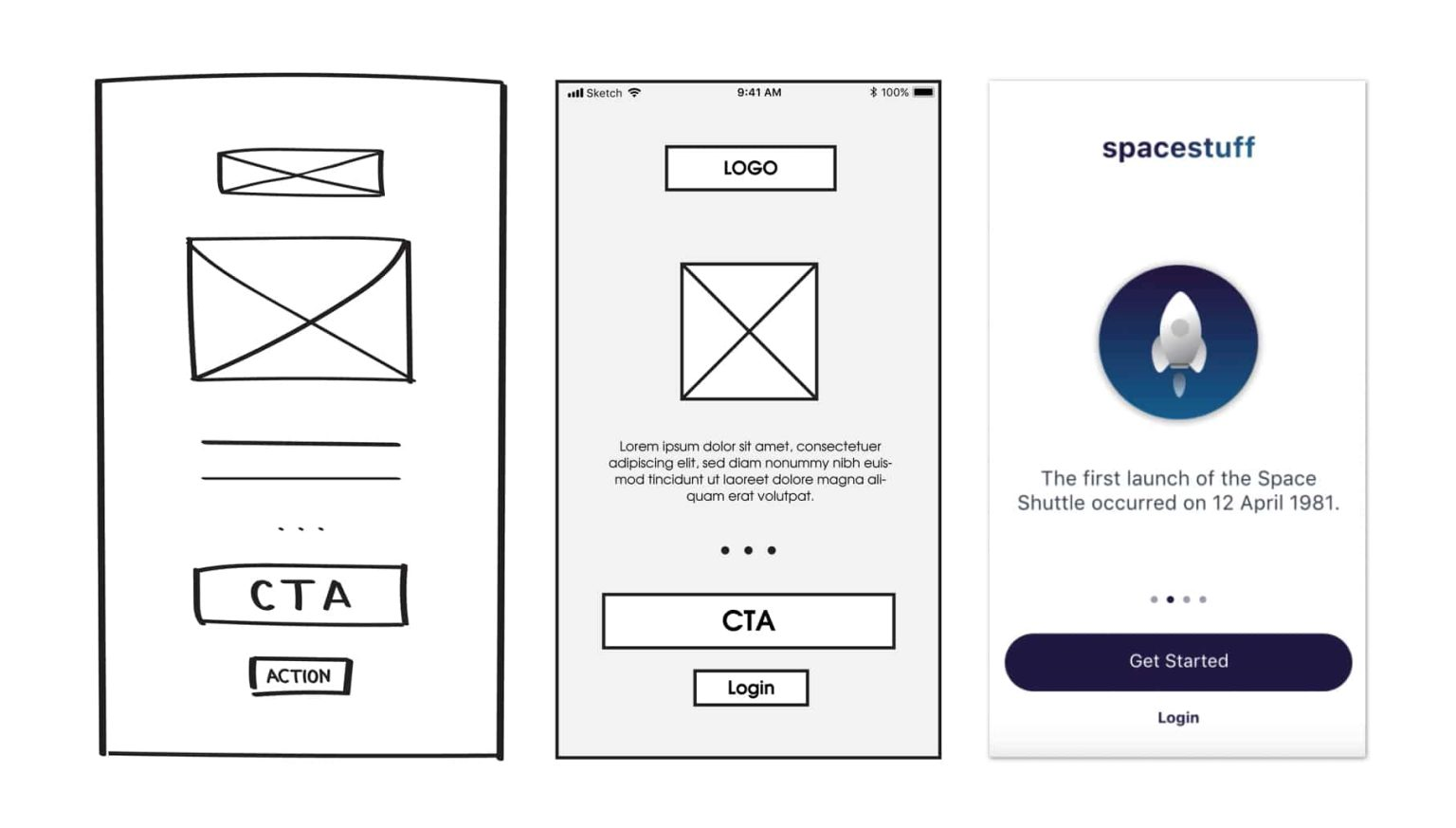

Levels of fidelity of visual designs:

- Fat-marker sketch

- Wireframe

- High-fidelity wireframe

- Clickable high-fidelity wireframe

You may find that you work your way up the levels of fidelity of designs as the vision for the MVP comes together - that’s okay!

I generally prefer clickable high-fidelity wireframes, as I find it helps identify gaps.

Image from this excellent article that illustrates the different fidelities of wireframes.

Once you get to this point, you may want to take your design to your customers and ask them for feedback.

It’s cheaper/quicker to make changes at the design step than the implementation step.

Technical Design

- Tech stack

- API/Resources

- Architecture

The Visual Design directly influences the Technical Design, so your developers can choose the best tools for the job.

Tech stack

”The collection of technologies used to build a digital product.” ~The Internet

- Programming language (ie, JavaScript, Python, Ruby)

- Framework(s) (ie, Flask, Django, Ruby on Rails, Express)

- Libraries (ie, visualizations, widgets, etc)

- External APIs (ie, Google Maps, ChatGPT)

- Tools (version control, text editors, etc)

Questions

- What libraries exist that we can take advantage of and save time?

- Do we have a “special sauce” that we should develop in house? (Most tech startups don’t, especially at first!)

Use what your devs know. Take on technical risk purposefully. Consider thinking about choosing technologies in terms of spending Innovation tokens.

A Note on Licensing

Typically startups build their products out of “open source and free” tools. These tools are available to use by their authors because they are licensed as such. However, not all code on the internet is permissively licensed. Be careful!

Here is a link to a list of common licenses and their implications.

Resources/APIs

”Resources” represent “what” is stored by the application (users, posts, etc).

”APIs” define “how” the resources can be interacted with and by whom (creating posts, deleting posts, etc).

Questions:

- What are the “resources” required by the design?

- What are the relationships between each resource?

- What actions should be able to be done on each resource, and by whom?

Architecture

How your tech stack is put together, and how/where it’s hosted (ie, the server).

Options:

- Cloud provider VS PaaS (platform as a service)

- Containerization (Docker)

Questions:

- Does the architecture satisfy your expected initial customer load?

- Do you have a path to scaling?

- How much does this cost now? At what point will it be more cost effective for me to move to something else?

Sometimes your architecture can influence your tech stack (ie, serverless).

I personally like the PaaS route to start.

Dev Youngstown’s Go-To Technical Design

- Domains: NameCheap

- Version Control/CI/project management: GitHub

- Web: React via Next.js, MUI components

- Mobile Apps: React Native via Expo, NativeBase components

- Backend: Python via FastAPI

- Database: Postgres

- Hosting: NorthFlank

- Error reporting: Sentry

Estimation

Unless your developer has built your exact product before with the exact same technologies, there will be “unknowns”, aka “risks”, in the project.

These risks each have the opportunity to cost a LOT more than estimated, and take a LOT more time. Make sure you choose these risks very carefully.

Typically developers break up their projected work into “tasks” aka “issues” aka “tickets” - the smallest chunk of work.

It’s not uncommon to start a task and discover that it’s actually bigger than expected, and needs to be broken down further. Often, the estimate of these smaller tasks adds up to more than the original task.

Your estimate is your last opportunity to make sure your scope fulfills your MVP goals:

- Proves the riskiest part of your startup

- Starts your “iteration engine”

- Built…

- Quickly

- Cheaply

- Maintainably

- Intentionally

It’s not too late to look at the estimate and cut parts that are not necessary to achieve the goals of your MVP.

Example ongoing cost breakdown

- Domains: NameCheap ($15/yr)

- Version Control/CI/project management: GitHub (4$/dev/mo)

- Mobile Apps: Expo ($30/mo)

- Hosting: NorthFlank (~$20/mo for DB and two worker servers)

- Error reporting: Sentry (~$20/mo)

TOTAL: ~$100/mo

However, this cost can quickly inflate to thousands a month given the nature of a project (data / bandwidth / compute intensive, or security intensive (HIPPA, SOC2, etc)).

Code must be maintained

To support the latest devices and to protect against security vulnerabilities, all code that touches the internet needs security updates on at least a quarterly basis.

This cost depends directly on the cost of your developers, but personally I dedicate roughly a day a month to upkeeping our dependencies at BlastPoint.

Implementation

Tasks

Tasks should be loaded into some sort of project management system (GitHub / Asana / etc).

Tasks should be roughly ordered by how soon they can/should be done. Tasks that block other tasks can be optionally marked as such.

Assignments

Developers can either grab a new task when they finish their previous one (Kanban), or developers can be assigned tasks on a weekly or bi-weekly basis (Agile).

CI/CD

Tasks to set up a system to “automatically test and internally publish the latest changes” (aka CI/CD, Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment) should be done as soon as there is something to test or internally publish (even if it’s a blank page). This will start you on the right track, as CI/CD are painful to add later in a project’s life.

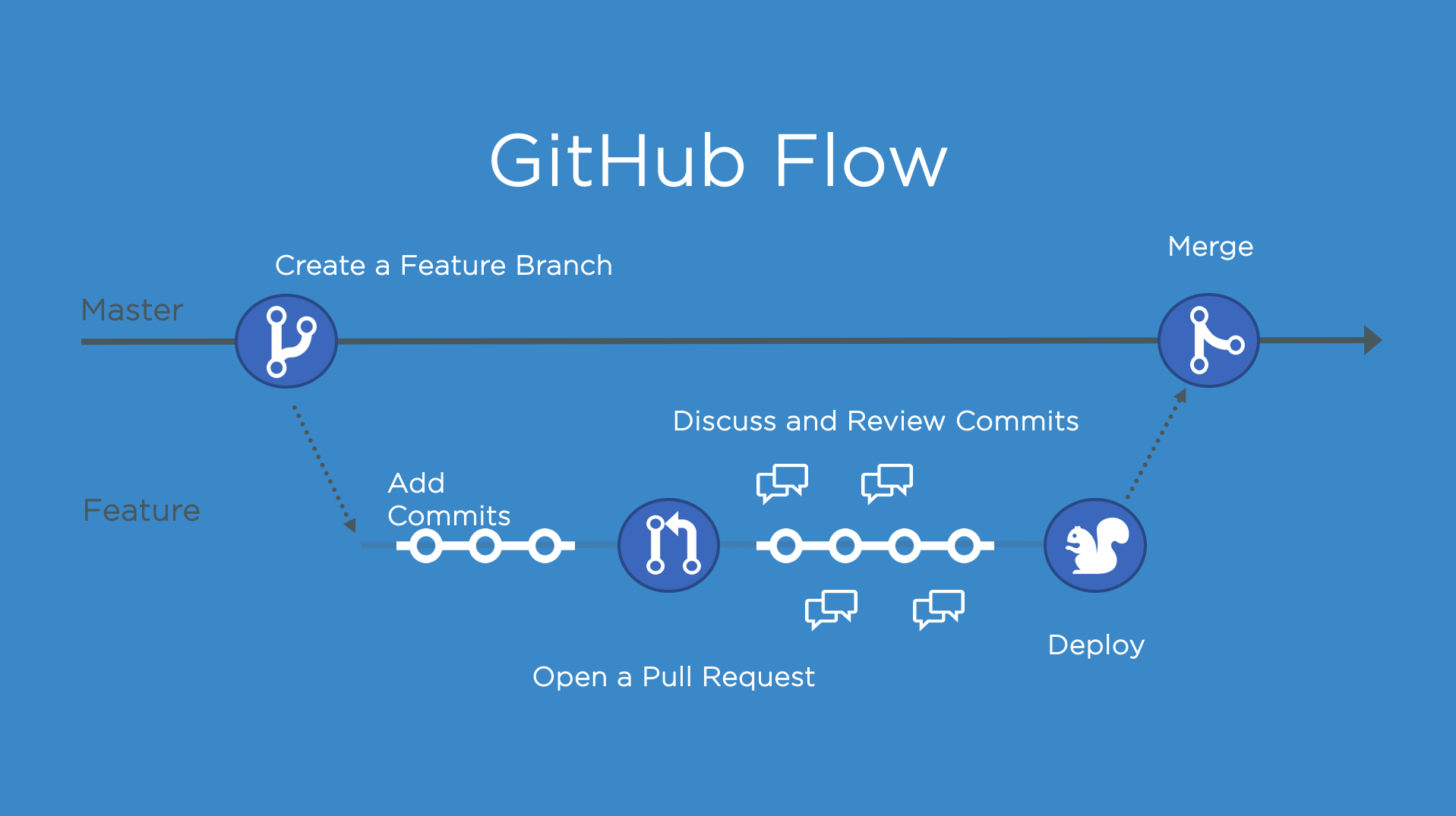

Workflow

Each task should be done in its own “working branch”. When complete, the developer should make a “pull request” (PR) of their proposed changes. At least one other developer should test and approve the PR before it is “merged” into “main”, which should preferably always be kept in a working condition. (This process is called “GitHub Flow”).

Having at least two developers allows this process to work effectively.

Image from this GitHub repository.

Exceptions

Everyone has their own way of working, but I have found that the above works really well. Feel free to deviate from it to better fit your organization, but make sure there is a good reason for doing so.

Last minute scope compromises

The last handful of tasks in an MVP can be painful.

Remember to focus on getting your MVP into your customers’ hands as soon as possible so that you can get feedback.

Last minute scope compromises are the least risky way to make sure your MVP is delivered on time and on budget.

It’s up to you to gauge your customers’ tolerance to bugs and incomplete features - it may be higher than you think.

After your MVP is done

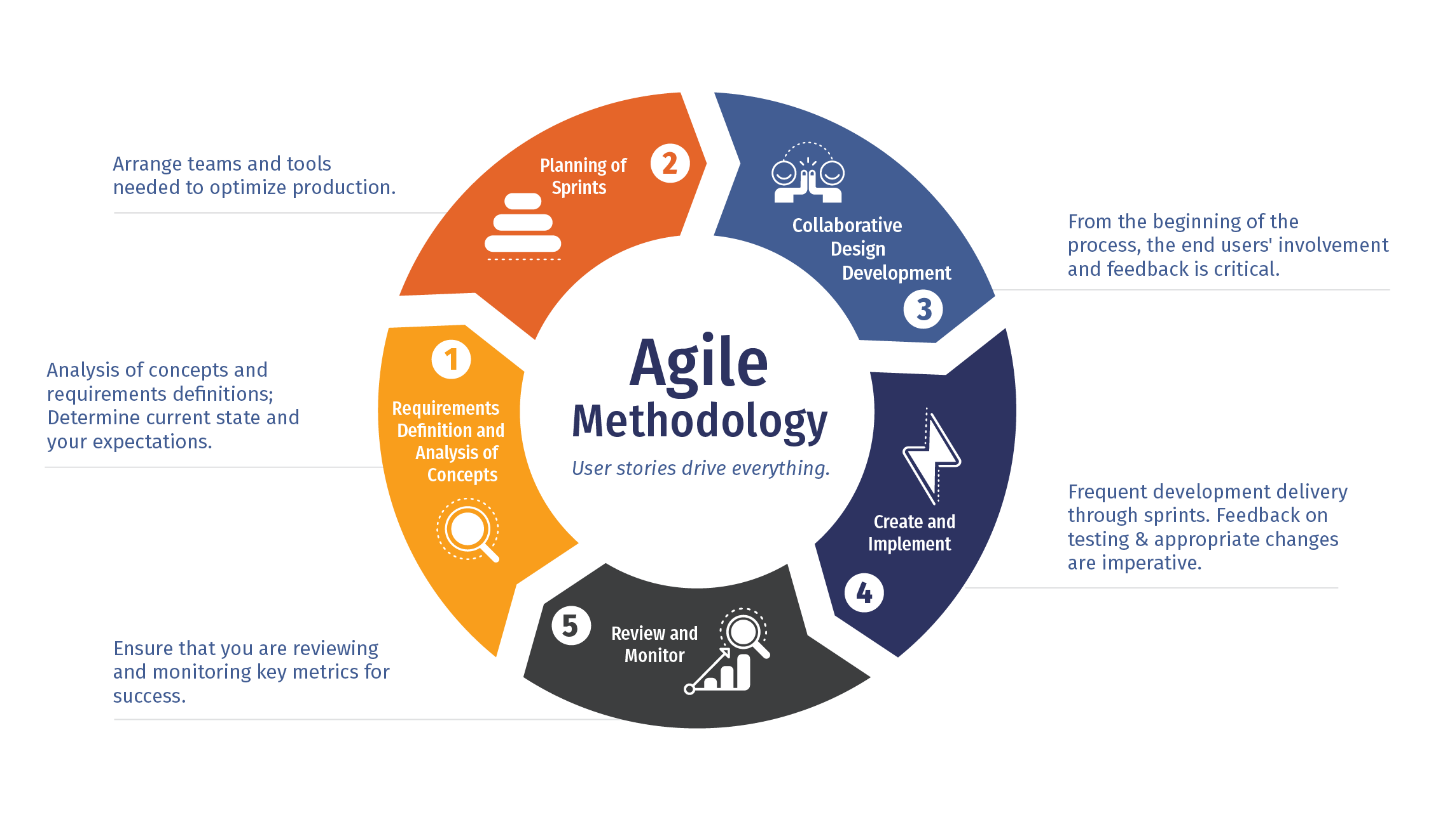

I believe that MVPs are by nature “waterfall” - they need to be comprehensively designed from the ground up, then executed with as few changes to the plan as possible.

However, once your MVP is complete you can switch to “Agile” development.

This is one of the reasons we want to build the smallest possible MVP - so we can “kickstart” the agile innovation engine as soon as possible.

What is Agile Development?

Agile development is the process of measured iteration.

The goal is to set a “sprint” pacing - typically two weeks - which acts as a time to re-evaluate what has been built and what is currently being built to make sure you are still working towards your organization’s goals.

Image from this article that illustrates the Agile Methodology.

How fast can my Innovation Engine run?

As fast as you can get customer feedback, and your developers can build on it.

Some of the largest organizations collect user data automatically and publish changes hundreds of times a day.

You’ll most likely be collecting user data manually - hopefully at least every two weeks. Publishing changes can happen at the same pace, or faster.

In house or contractors?

- If software is not your competitive advantage, you may be able to get away with using contractors.

- If you are a non-technical founder, your software is probably not your competitive advantage. (It’s probably your way to market or your industry experience!)

- You will probably still want a senior technical person reviewing contractor work for quality.

- If software is your competitive advantage, you probably need to bring in a CTO and give them significant equity.

Tips for hiring software engineers

- Stock options are no longer a sufficient substitute for competitive salary - you need to offer both.

- More senior person architecting and splitting up tasking.

- Less senior people can do the actual work.

Video

A recording of the talk I gave the for the Youngstown Business Incubator that inspired this blog post.